Interview conducted by Anca Truțesko

Mihaela Ionela Cîmpeanu was born in Băilești, in southwest Romania, in a family of young Roma. Her father came from a family of bricklayers and became a construction worker. Her mother was unemployed. She is the eldest of the family’s five children. When she was one year old, they all moved to Craiova.

She attended middle school and then high school, where she discovered her talent for drawing. She was then admitted to the Arts High School and graduated with the highest grades. After graduation in 1999, she attended a public administration course.

In 2000 she moved to Bucharest, where she attended a journalism course and specialized in press photography. Later, she worked at a Bucharest newspaper, “Curierul Național,” and as a painter at the Buftea film studios. She graduated from the Faculty of Sculpture at UNARTE Bucharest. Her work was featured in the “Paradise Lost” exhibition in Pavilion I Rome, curated by Timea Junghaus for the 52nd International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia in 2007.

When did you discover your direction toward the arts and at the confluence of which ideas you is your artistic practice?

I have liked to draw since I was little. I remember that since the 5th grade, one of my favorite subjects was drawing; when the teacher gave us an assignment, I did three or even four instead of one drawing. Even though my pictures were much better than my classmates, I would get a low grade, usually an eight. Then, in the 8th grade, I signed up for the painting course at Palatul Copiilor, where teacher Vieru Valerică, who was teaching then, asked me which high school I wanted to attend. I told him I wanted to go to an economic one with a gastronomy profile. At that time, I dreamed of being a chef, but it seemed fate had prepared a different future for me because Professor Vieru told me I had to attend Art High School. So we went there together, where I was given a quick drawing test and it turned out that I was even better than the children present at that workshop hour. That is how I managed, with the teacher’s help, to start the free preparation for admission to the Art High School in Craiova. I finished a professional college and a master’s degree in art.

Through my works, I touch on subjects that are pressing both on me and those around me. Even if I do not consider myself part of an artistic current, I create because I feel that way. After all, that is how I translate my feelings and thoughts.

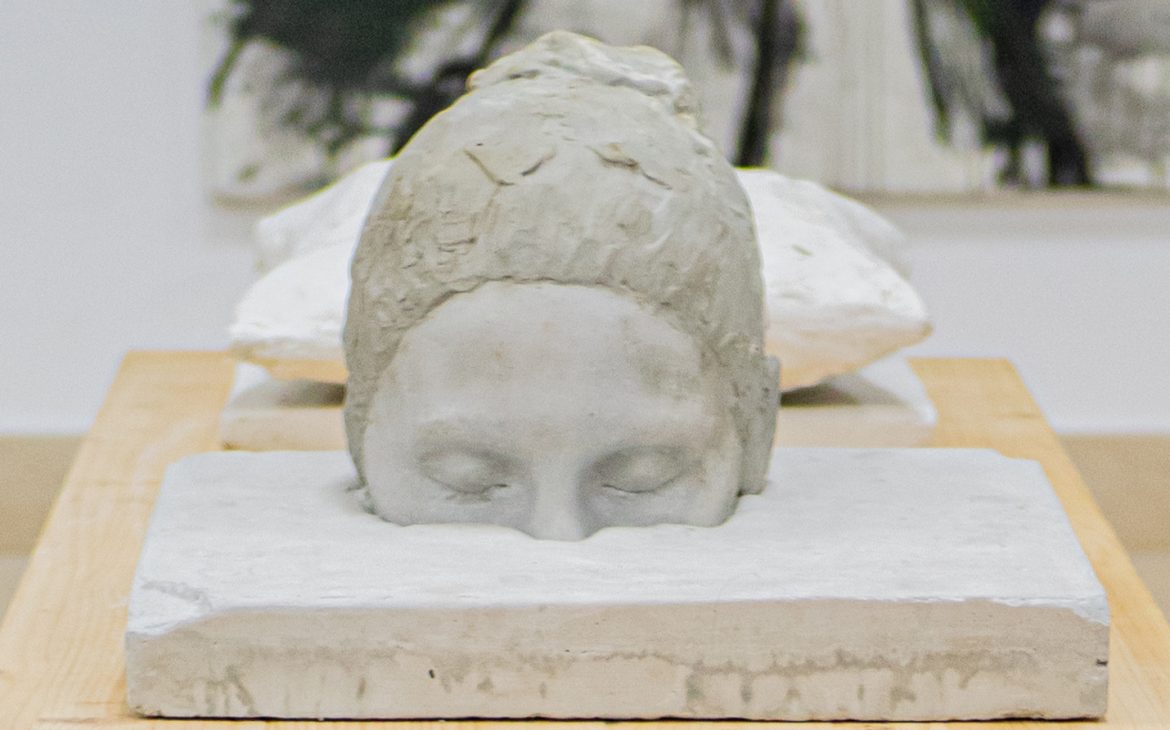

Work presented in the collective exhibition “Chronic Desire”, part of the RomaMoMa project, Timișoara 2023

Artist and mother – how do you manage to combine them? Both require time and dedication.

This is true. Being a mother and an artist takes a lot of time, and I think it was not easy to combine them. Now that the three have grown up, I also have time for myself. I have gradually returned after quite a long break, and now I can create at total capacity.

You participate with an artistic installation in the group exhibition “Lockout Stereotypes. Counter-cliché”, an exhibition event that brings together six artists from Romania and Norway, whose practices and visual discourse aim to combat stereotypical mentalities and social segregation resulting from prejudices against Roma women as well as other minority groups. How did the collaboration for the project begin?

It all started with a simple phone call about the possibility of applying for this exhibition. After the selection, I was accepted, and I was glad that I decided to enroll. It is the first collaboration with Andreea Capitanescu, the exhibition curator, and the Ames Association.

Your work communicates so vividly with visitors. What is the essence of this Santa sangre of the installation? What inspired you? Tell us something about the unseen process of the work.

I am always concerned with knowing that the visitor can interact with my works to create a connection and convey to the viewer, the art consumer, the feelings and message transposed in the work.

I had this idea imprinted in my mind for a long time, like we are all the same, regardless of outward appearance, but I had not found the right opportunity to realize it. This idea is constantly evolving, and I want to take it as far as possible. If we strip away everything that makes us different, all this packaging/skin that supports everything inside us, we find a network of blood vessels that keeps us alive. This fluid that flows through them unites us because it does not consider appearance, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, etc. For example, when a blood transfusion is needed, it does not matter who the donor is or his job or background. His color is the same whether his skin is white or black.

The works in the exhibition are diverse but have the same voice. How would you describe the collaboration with the other artists, and especially, what is the common ground with Margaret Abeshu?

I am thrilled that one of my works is part of this exhibition and had the opportunity to present my idea. Regardless of gender, nationality, or orientation, we are the same because the same red liquid flows in our veins.

Even if they are different, the works in the exhibition have a strong connection in that they are created by women who have faced discrimination in many ways. Either because they are of this gender, because they have a different ethnicity than what is accepted in society, because they have a specific appearance, or because they have a different sexual orientation.

Can you give us an example of a situation when you were discriminated against on a professional or personal level based on ethnicity and gender? How did you cope? The exhibition aims to combat such toxic discriminatory mindsets.

Oh, there are many situations in which I have been and am still being discriminated.

First of all, through the lens of the fact that I belong to another ethnicity, then the fact that I am a woman. However, what hurts the worst is that type of discrimination when people of the same race do not accept you because you spend too much time with Romanians – as if I had given up my roots; then, when the Romanians tell you that you have nothing to do among them and to go where you belong.

Work presented in the collective exhibition “Chronic Desire”, part of the RomaMoMa project, Timișoara 2023

The first time I experienced what it means to be discriminated against was in high school, from day one. I tried to ignore it and get over it, working hard to prove that I was better than them, significantly better than the boy who insulted me and who, after all, was my classmate all through high school.

There were times when at work, as I was a teacher of Drawing Studies at a specialized high school in Bucharest, I would enter the chancellery, and there would be silence. Through work and respect, I proved to them that I am a person of integrity. I had to work twice as hard to establish myself and be respected.

Can art change the world for the better?

Yes, art can improve the world, even if it is more complex.

The exhibition “Lockout Stereotypes. Counter-cliché”, inaugurated in the WASP space in Bucharest, is currently on display at the Ploiesti Art Museum and can be visited for free until July 25, 2023. With what attitude do you recommend visitors to look at your work and the exhibition?

First, the visitor should put himself in someone else’s shoes and understand that that person is just like him. Then try to strip, hypothetically speaking, of everything he has on, including skin and muscles, and discover a heart that pumps 24/24, the red blood found in every human being, regardless of his physical appearance, ethnic, religious, sexual, political, etc. The visitor should take a moment and realize that blood does not account for all of the above.

Photo credit: Cristian Farcaș

The work was presented for the first time in the International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia in 2007