Interview conducted by Evantia BARCA

Evantia Barca spoke with Gabriela Mateescu, artist and initiator of the project, to document the UAP studios in Romania about the motivation behind the project and what the Studio means to Romanian artists.

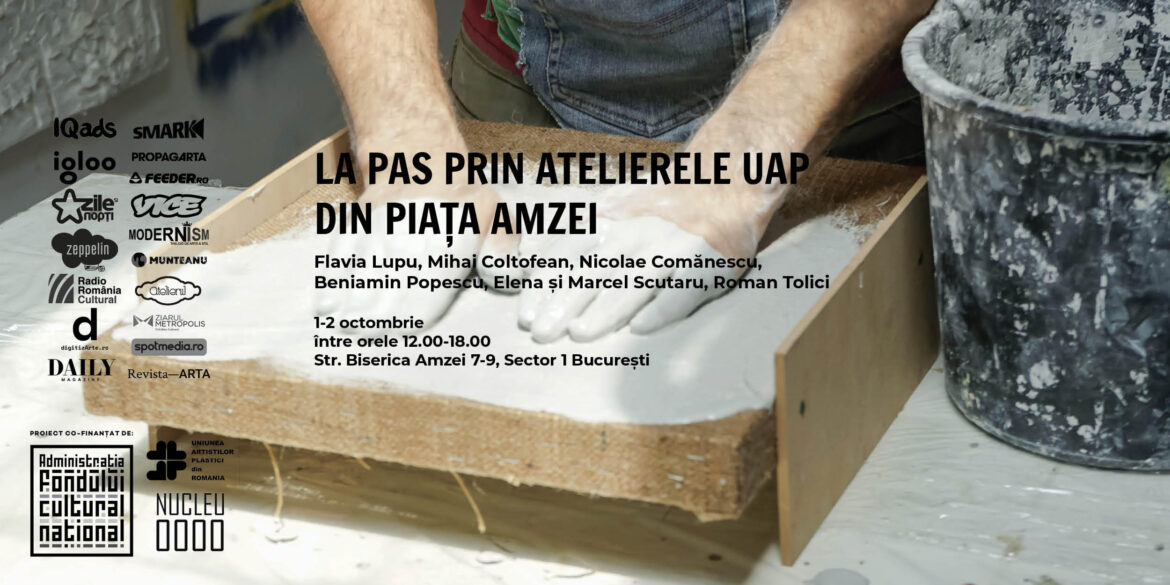

The “Walking through the UAP studios/ La pas prin atelierele UAP” program in Romania takes place this year from June 23 to July 16, 2023. It includes exhibitions, debates, and guided tours in the buildings of the Plastic Artists Union in Bucharest, Râmnicu Vâlcea, Arad, and Timisoara. Dozens of exceptional artists will open the doors to their creative universe: the Studio.

Gabriela Mateescu is interested in the artist-run community and how artists self-govern and create together. The group she formed nine years ago, Nucleu 0000, already has a relevant portfolio of projects, most focused on a process-based practice, creating opportunities to meet and collaborate in artistic communities.

In 2022, Gabriela coordinated research for ARTA magazine about artist-run spaces in Romania and initiated several educational and cultural projects, usually dedicated to current critical themes.

From gender-based accessibility differences, she was once addressed with “Where is she?” (a public awareness project regarding the lack of artists in the permanent collections of museums in Romania) to the documentation of UAP studios at the national level and the archiving of this information, an approach aimed at raising awareness of the importance of artists for the development of communities.

Together with Taietzel Ticalos, initiated and coordinated the “spam-index. ro” project, a platform to promote Romanian digital art. The Nucleu 0000 Association is a collective of artists brought together to offer meeting opportunities based on process and collaboration.

Evantia Barca: “La pas prin atelierele UAP“ has a double role: to promote art and publicly discuss the issue of creative spaces. The story of these workshops is, in places, an action movie, with legal battles, accusations of bias, illegal rollbacks, protests, negotiations for redevelopment, or requests for additions. What is the current situation of these spaces at the national level? How much are they, how can they be obtained, and who can get them?

Gabriela Mateescu: The subject became interesting when I received a UAP workshop nine years after I had enrolled in the Union. I got it because it was in an advanced state of decay and had already been rejected by several. It had been about nine years since I had finished college, and I had never worked in another workshop, only at home on my laptop. I was waiting for it as always. Due to legal ambiguity, the space is in a building that may no longer be artists’, although creatives of all kinds have been working there for over 50 years. This was the first trigger for me.

The workshop is a vital landmark in an artist’s life, which is why it is a topic we constantly return to in discussions. All these years, colleagues who have private workshops told me they keep changing them, either because the rent is increased or because they are evicted because the owners want to sell or rent at higher prices. This dynamic remains valid for private homes – workshops in apartments and houses, but especially for large buildings – let’s call them “industrial.” The latter is more suitable because artists need large, comprehensive, high spaces closer to the hall type.

Block apartments are, from this perspective, somewhat inappropriate. Artists come, create value in all kinds of abandoned and devastated buildings, modernize them, bring them to the public, and, in this way, attract the attention of investors, so they are eventually evicted. I had all these questions during the period when success stories such as the Brush Factory and the Interest Center in Cluj, the workshops at ISAF Bucharest, the stuudios on Popa Nan Street Bucharest in the Mătasei Populare building, and others like them came to prove that it is possible.

What we wouldn’t give for a workshop at the UAP, we said to ourselves, where we could sit without worrying about being kicked out. To have a workshop at a price we can afford.

From here, I started documenting the UAP workshops and creative spaces that were once important but also lost, by the hundreds, after the Revolution, due to litigation or administrative decisions. Let’s say you are safe here. The UAP does not kick you out of the workshop, but the authorities might. You see, the Union could not own buildings during communism, although it was a successful, very wealthy institution that supported all the artists in the country. Although the Union built many, workshop buildings were named after various state institutions. After the Revolution, the buildings were placed under the authority of local town halls or multiple ministries. Many others were retroceded. Being often central buildings located in crucial places of cities, generally heritage buildings located in areas where rents are very high, town halls have more interest in kicking artists out under various pretexts, most often “renovation” or “consolidation,” so that once the spaces are vacated, the artists will never return.

Evantia Barca: Have you documented these situations? Do you have some examples?

Gabriela Mateescu: A recent incident occurred last year in Constanța, where the town hall wanted to evacuate the artists from the workshops. The artists united and made a press conference and a big fuss, and under public pressure, the workshops remained under the administration of the UAP. More here.

In 2013, another protest by Timisoara artists in front of the City Hall signaled the impact of the rent increase and the risk of losing some. The authorities said then that “Timişoara City Hall is not a communal cow” for artists to milk. This was their view of artists as parasites, and they found it rational to align studio rents with the “market rate.” Considering the buildings’ central location, the workshops’ rents should have been in the thousands of euros. Again, the artists united, protested in front of the town hall and the galleries, and the mayor relented.

More about the incident here

The same thing did not happen in Craiova, my hometown, where the mayor’s office, under the pretext of “renovating” the workshops, kicked out the artists from the workshops in Romanescu Park. Currently, there is a risk of evacuating many workshops in the country.

This is the context in which the interest in this subject grew organically. Many of my colleagues believe the topic would be relevant to the public agenda. So far, only in the arts community, although cities and citizens alike should be interested since any contemporary urban development relies on culture and creative communities for growth. It may be a good time for artists to take the initiative. I have been organizing various cultural events under the umbrella of the Nucleu 0000 Association for more than nine years, and the idea of a union of a collective of self-administering artists is very close to my practice.

I have always been fascinated by the idea of a community that organizes exhibitions, lives together, and creates art, fighting for its rights with the state and the authorities.

Evantia Barca: Could we someday have strong organizations in the field of visual arts, able to create rules about the state and the guild? I am thinking now of the British unions in movies which – to evoke a detail of a giant puzzle – block from the beginning of the production, the amount needed to pay the actors and check at the end if the fees have been transferred…

Gabriela Mateescu: In visual arts, several international organizations fight for artists’ rights. The first one that comes to mind right now is the IAA/AIAP (International Association of Art)

As far as I know, it includes most unions, and organizations that defend artists’ rights globally and consult UNESCO on how art can be helpful. I believe it was formed at the Third General Conference of UNESCO, held in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1948. The Director General at the time was charged with investigating “ways in which artists might serve the purposes of UNESCO” and discovering what social, economic, or political obstacles might stand in the way of artists practicing their art. The association was also tasked with recommending measures to improve the working conditions of artists and ensure their freedom. I am interested in the subject; I always get news about what the artist unions in Puerto Rico, Slovakia, Greece, or Turkey are doing.

Artists’ communities and collectives are topics of interest to me, and beyond public interventions, I have been studying them quite seriously for some time. I am fascinated by artist-run spaces and associations that fight for artists’ rights; I dreamed, with my collective – Nucleu 0000, of being able to contribute to changes that would impact my generation. Last year, I also coordinated a Dossier in ARTA Magazine about artist-run spaces in Romania after the Revolution. The union, which already has more than 100 years of history, is an excellent example of the theme: artists once united to fight for their rights. We are talking about over a century in which a professional organization of artists has shaped the field of visual arts.

On March 12, 1921, the Fine Arts Union was established due to the initiative of artists led by Artur Verona, Camil Ressu, and Teodorescu-Sion. Through its merger with the Mixed Union of Artists from the province, the Union of Plastic Artists was created on December 25, 1950, as a legal entity of public utility, an act enshrined by Decree-Law 266.

Since college, I have been drawn to the Union and understood it mainly as a symbol of the Union struggle. However, it is easier to understand it from the perspective of concrete, immediate interests. From the latter view, the hope of having a creative workshop is probably one of the main reasons many decide to become members.

Evantia Barca: In the end, how important is an artist’s adequate creative space? What is an artist’s connection with the studio, and how much does it influence his work? You could also give us some examples, especially since you have already documented a relevant series of workshops.

Gabriela Mateescu: The documentation of these workshops was inspired by the artist’s drama without a workshop. I want to point out that it is an endeavor that I carry out with personal momentum under the umbrella of my association, not the Union. First, I want to show both the public and the authorities how hard artists work in these spaces and how important it is to have a stable center of their creative universe.

Many contemporary artists are already known on international stages, but also many who work more locally exhibit in UAP galleries and create in workshops frozen in time.

We promoted a new type of event for them, open workshops, a formula so often found in workshops or private studio buildings in the West.

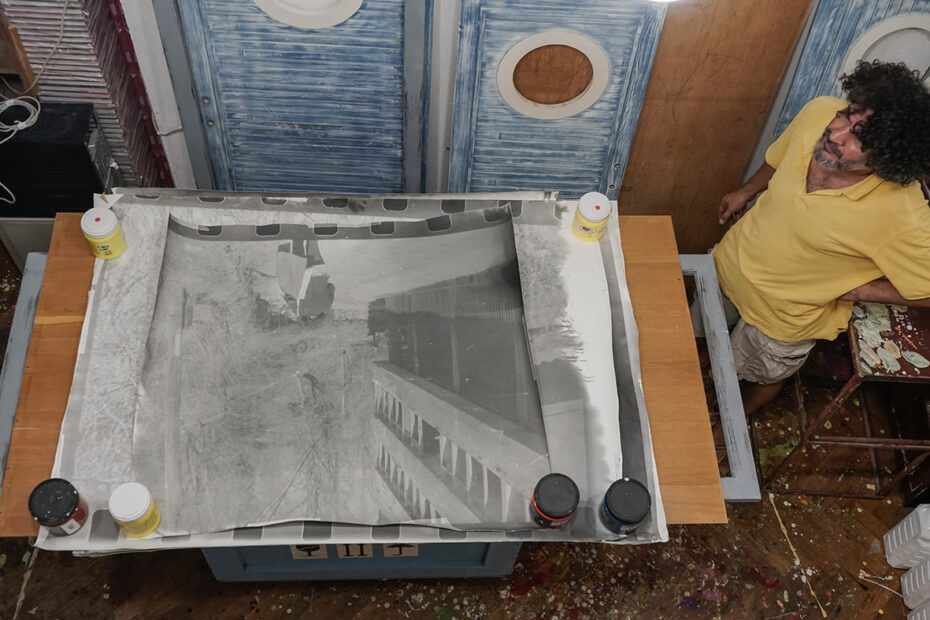

The audience enters dozens of universes stopped in time, spaces defined by ideas, turmoil, and failures. A workshop inspires you with beautiful stories that transport you to other worlds, other eras. No workshop is like another. They are either orderly, like an art gallery, with the canvases impeccably lined up, or messy, stained with paint, piled up with piles of work. Some are as big as a studio, others as small as a storage room, some flooded with natural light, others without windows.

They are hidden in historic buildings with a red dot, new or restored buildings, apartment blocks or basements full of moisture, or in chic, impeccably arranged areas. I have already entered more than 50 workshops in four cities, and how each artist has put their space, according to their way of working, is downright fascinating.

Evantia Barca: Who and how can someone get these workshops?

Gabriela Mateescu: In principle, the workshops can be obtained through a request, but many such spaces are significantly degraded, so the new tenants have to refurbish them. Some have debts from former tenants, so their situation needs to be resolved, and sometimes the utilities are reconnected. The request is determined according to availability so that you can wait months or years. Various opportunities arise occasionally, but it depends on how much the artists are willing to invest in them, how they find out about them, and if they follow the announcements on the site that one has become available. Many assess whether the premises suit them in terms of size, location, or other particularities, such as the fact that they are on the top floor without an elevator, which could be an essential detail for some.

Three years after becoming a full member of the Union, I met young artists who managed to receive a workshop. Young people usually get the most dilapidated workshops because they are the most willing to invest in them. They think that, over time, they amortize their expenses since it is about spaces allocated for an unlimited period, with annual contracts.

Somehow, the idea that they are granted life has slowed down, which is a good thing and a bad thing at the same time. Good, because you are sure you have your workshop, in which you invest and arrange it as you like. Too bad because there are so few of them, and it takes decades for one to break free.

I, for example, received a workshop so degraded that it took more than a year to set it up. I did not have the money to hire professionals to fix it immediately, so I cleaned it myself. The room is in the attic, in an old building, with holes in the roof, through which it rains, and there is a lot of mold. I can make out a strange picture with a missing ceiling and a narrow, spiral staircase that one can hardly climb up or down, let alone with a bulky object.

This may have been luck because it is clear that it would not have been a good space for large-scale sculpture, ceramics, glass, or painting. We received the studio upon the death of the former tenant artist, aged 79, who had the studio for about 40 years.

Evantia Barca: Is the situation similar in Vâlcea, one of the cities where you are opening workshops this year? What is the role of the Union at the regional level, particularly in Vâlcea?

Gabriela Mateescu: I launched this project in 2022, right in the building where I received the workshop, because I wanted to get to know my colleagues better and the public to know us. My workshop was still being prepared when I organized the first edition, although I had planned the event that way. This year we will continue with the “Borcan” building in Bucharest, which houses more than 50 workshops and warehouses of works on the first five floors. It has become a cause of concern for artists, who fear they would be lost if the building was reconsolidated.

I was curious to learn more about the country’s workshops and their history. In dialogue with Gheorghe Dican, president of UAP Vâlcea and responsible for UAP branches in the country, I selected the other three cities. He told about the few workshops built by the UAP after the Revolution, set up in Vâlcea. Following the requests for workshops submitted by four artists from Vâlcea, the management of the Râmnicu Vâlcea Branch of the Union of Visual Artists from Romania began in 2007; the necessary steps with the Town Hall of Râmnicu Vâlcea identify suitable spaces for this purpose.

The designated building, a former thermal power plant located right behind Secondary School No. 5, was in an advanced state of disrepair after several years of abandonment. The redistribution and redevelopment of the space was done partly with the financial support of the City Hall, partly from the branch’s resources, according to a project made by the architect Corneliu Crașovan.

The transformation of the former thermal power plant, of which only the outer walls remained, into the four beautiful workshops that now exist required a lot of work and effort, completed in 2010 with their handover to the beneficiaries and the granting of free use of the building by the City Hall for the Râmnicu Vâlcea Branch of the Romanian Plastic Artists Union.

I chose this city to give an example of good practices regarding the involvement of the authorities in the town’s cultural life. I then went to Timisoara, where there are 32 workshops for 270 artists. The city hall here has not, over time, been as open to artists, nor has it considered the workshops to be important to the city’s cultural value. The last two mayors were urged to solve the problem, and even during Robu’s administration, there were protests because the mayor’s office wanted to participate in the workshops. And now, in the year of the celebration of culture in Timișoara, several artists fear that the mayor’s office will take away their workshops, as they are spaces in central buildings. And where although billions have probably been spent on short-term projects after the cultural capital event ends, not a single workshop will be added.

At the end of our circuit this year, we will stop in Arad, which is another particular case. The president of the UAP in Arad managed to build eight new, spacious workshops because he thus negotiated the demolition of the former workshops on the site, which the municipality wanted to create a parking lot. The town hall did the new workshops in terms of this exchange. I was interested in the story of these negotiations and how the local structures agreed that the workshops would be preserved. There are, however, also defeats in Arad. In a process that has been going on for several years, there is a chance to lose the two local galleries: Alfa and Delta.

The four cities offer various models of working with local authorities. We remain, however, some observers who want to archive, albeit a bit late, the stories from the creative spaces. As I said, the project is independent of the Union and looks only from the outside. But I listened to all these stories. The artists talked for hours, and their stories filled novels.

Evantia Barca: What is the cultural offer of this section of the project, and what is the selection of artists?

Gabriela Mateescu: This year, we will also have the exhibition concept launched last year. We selected four artists from each city who already had a UAP workshop, and they worked in a team with four other artists who did not have workshops or private workshops. The goal is by no means an aesthetic one, to create exhibitions “pleasing to the eye,” but rather to create dialogues, relationships between artists, and links that may be useful in the future. I have always been more interested in the process side. The 24 artists, 8 in each exhibition from Bucharest, Vâlcea, Arad, and Timișoara, will produce works or find older works that respond to our discussions, inspired by exchanges of ideas.