Béla Zoltán (b. 1977) is a contemporary artist who masterfully oscillates between figurative painting and transforming found objects into authentic contemporary art pieces. Upcycling is how he taps into freedom, inspiration and creative power, turning a discarded object into a masterpiece. The artist is passionate about transforming objects, oscillating from preserving memory and patina to changing through different technical processes, challenging the viewer’s gaze and thinking.

Through this interview, I aimed to explore the artist’s concept and reasoning behind upcycling interventions.

Raluca-Elena Popa: When did you start to see a concept and artistic potential in abandoned, old, worn, or unused objects prone to inherent destruction but by no means to a new, artistic life?

Zoltán Béla: I graduated from the University of Arts and Design in Cluj-Napoca in the Painting department in 2001, although at the Arts High School in Baia Mare, I attended the Ceramics department, being fascinated by objects and working with the material: clay, plaster, and so on.

Over the years, in addition to painting, I also flirted with (found/collected) objects. But, in fact, I have always loved old, abandoned, patinated or rusty objects, characterized by a special memory!

Starting with stories from my childhood, my father was an amateur collector of ceramic objects, which he exhibited in the kitchen and the hallways of the apartment in Baia Mare, and my grandmother, also a painter, had extraordinary objects inherited from her parents and her grandparents. Since I was little, I would find objects in my grandparents’ yard or in different areas of the city, which I would keep or subject to various experiments.

Later, in the faculty, during the courses held by Mr. Prof. Florin Maxa, I was supported to experience both abstract and object painting. It was my first time experimenting, and it was exciting! I took a rake and a shovel from my maternal grandparents and painted them blue. Thus, I transformed the used objects into picto-objects by painting them with color (that blue leitmotif from the artist’s soul).

R.E.P.: Any object can hide an artistic concept by transforming it into a favorable context, or are certain objects privileged?

Z:B.: Certain objects speak to me. Sometimes, from the first moment, I realize what artistic idea characterizes them because I feel that they have potential.

Lately, I’ve liked certain objects on the internet and purchased them to transform and recontextualize them. Upcycling leaves the artist free to handle any kind of object, which is really beautiful. A wire, a stone, wings, sheet metal or even new materials such as cement and resins find their place behind upcycled concepts.

R.E.P.: Looking at your objects, are they brought from your past, or do they have a vernacular, collective imprint?

Z.B.: The objects that find their place in my workshop come from both sources. I am interested in capturing both personal histories (specific to me and my family) and shared histories of the city (represented by architectural fragments) or even memories of people I don’t know.

For example, one of the workshop’s most recent works received a recontextualization. A fragment of a broken capital found in the city was joined to a ball, also found, and patinated with a little white to make it look older than it is.

Another work also features a faded ball, found and preserved as it is. Time and seasons have worked upon it, petrifying it and giving me the involuntary feeling that it is made of concrete. Sometimes, their memory is preserved, and sometimes, it receives new information.

R.E.P.: Your objects are collected, manipulated, and altered by intervention and technological spells. If, for Marcel Duchamp, the first principle of indifference in the choice of his ready-made objects (selected, declared to be a work of art and unaltered), what is the criterion for choosing your objects? What attracts you to an object? What characteristics should he have?

Z.B.: My criteria for choosing objects come from within me. Sometimes, I feel I have to choose them; other times, they find me.

Sometimes, I walk around the different parts of the city and notice abandoned objects on the ground. I never vandalized a building, but simply, my eyes went to discarded things. I like to bring them to the workshop and keep them until they find a role and an interpretation of an artistic concept.

Zoltán Béla, Kisellef, 2022, electric panel door, Austrian crucifix c. 20th. Image credit: New Folder.

The easiest way is to exemplify my thoughts with a work from the workshop. A few years ago, I found the door of an electrical panel lying on the ground near Kiseleff Park. It had a special beauty, was patinated (rusty), and contained the high voltage symbol sticker. Bringing it to the workshop, I remembered the Catholic crucifix, probably from Austria, bought in Bucharest and the possibility of joining them in an artistic context. I attached it to this metal door, and it blended perfectly! The color of the wood harmonized exceptionally well with the rust, and I felt like they were together forever!

R.E.P.: Considering that the objects you find have their own memory hidden in their materiality (the so-called patina of time, for example, rust), do you intervene on them by cleaning them and bringing them to their original form, or do you preserve their individuality from the moment they were found?

Z.B.: Actually, the decision to transform starts from how these objects speak to me and how much these objects inspire me. I keep them intact if they can convey a certain concept from the first moment. If the objects have a certain memory or patina, I highlighted their characteristics and intervened as little as possible on them. In this way, the objects found in the city space are washed and cleaned of the accumulated energy. If, instead, there are new objects, such as ready-mades and tools, I paint them or intervene on them to integrate into a desired theme and, at the same time, to express my ideas.

R.E.P.: Compared to Deconstructivism which involves dismantling, fragmenting, reassembling and reinterpreting objects, in a non-conformist or abstract way, upcycling assumes that the original form is preserved and the object is recognized; to be able to see what it was and also what it has become, even if it has a technological intervention on it through processes, methods and operations, such as: smoothing, descaling, patina, burning, softening, shining, polishing, retouching, etc. How does the work begin and evolve, from concept to realization, in your creative process? Do you use sketches, knowing clearly where it started and how it will be finished, or do you let inspiration and practice drive you?

Z.B.: Every upcycled object contains an idea! Depending on how the objects communicate with me, I look at some and know exactly where I want to go with the representation of the artistic concept. For others, I make sketches, and some I put aside until they find their calling in the first phase, their finality being unknown.

Starting from the question, upcycling subjects me to preserving as much as possible the appearance of the object and bringing it to a better level, which is where the term up actually comes from, placed in antithesis to down. Through downcycling, the object is so much modified and destroyed that its original form can no longer be distinguished, it can no longer be used, and it becomes waste; it pollutes.

R.E.P.: Considering that in Modernism (20th century), the idea is that the object’s shape comes from its function, we can say that texture and matter become a source of meaning for your art. Can an object lose its personality by changing its original texture?

Z.B.: Rather than the form itself, I play with its appearance, texture, and symbolism. Many times, my intervention accentuates the objects’ symbolism and story.

R.E.P.: Do your objects change their meaning through concept and technological intervention on them, but also through association with other objects? What is the reasoning behind the assembly and juxtaposition of antithetical textures: soft-hard, shiny-matte, old-new?

Z.B.: When working with objects, I juggle the antithesis of textures, such as warm-cold, shiny-rough, or even metal-taxidermy (metal/chrome vs. stuffed birds).

I will give two answers, using works present in my workshop, for example, Space Unicorn. I bought a satellite dish from a recycling center that had once picked up the waves from space. Although it was rusty, I decided to turn it into a symbol with chrome plating. It is now extremely shiny, and in its center is a cow horn.

The other work was exhibited in 2014 at the Bucharest Biennale and is composed of two completely different works: a Russian helmet, extremely rusty, from the Second World War, which I nickel-plated and chrome-plated, becoming a very shiny object. Although I really liked how it looked, I preferred to work on it while still keeping its flesh/metal shape that indicated its provenance. Later, I attached two mousetrap wings to it, and it changed its purpose. The symbol of flight and the bird was highlighted by mirroring the wings in its radiance.

The way the different textures harmonize actually supports my artistic concept and the symbolism behind the objects.

R.E.P.: I noticed that behind the upcycling objects, there is a game of gloss and textures, shadows and lights, but also a chromaticism based on earth tones, grays, blue, black, and white. How would color (strong/flashy tones) influence your artistic concept if you were to use it?

Z.B.: Beyond being an artist passionate about collecting and transforming objects, I am a painter and feel color naturally. I really like antitheses, contrasts between warm and cold or between complements, and the meeting between grays and colors. In fact, I believe that those strong or fluorescent colors are not found within my being. I don’t find myself in the contrasts between very strong colors but, on the contrary, in the harmony of pastel colors and colored grays.

R.E.P.: Your objects receive an aura of uniqueness, being removed from their usual use context, giving them an artistic concept. What are the themes you approach throughout your artistic creation?

Z.B.: Each personal exhibition is structured around a theme encompassing several works. Over time, I juggled several themes, starting from childhood and family, freedom and independence, time and its passage, the fusion of old and new, the antithesis between the sacred and the profane, the contrast between ancient and contemporary or the opposition between nature and man-made (the work tools: shovels, rakes, scythes) or religious themes such as sacrifice, Christianity and God. Sometimes, I also use the contrast between the psychological states that the objects express, such as positive-negative, good-bad, and happiness-depression.

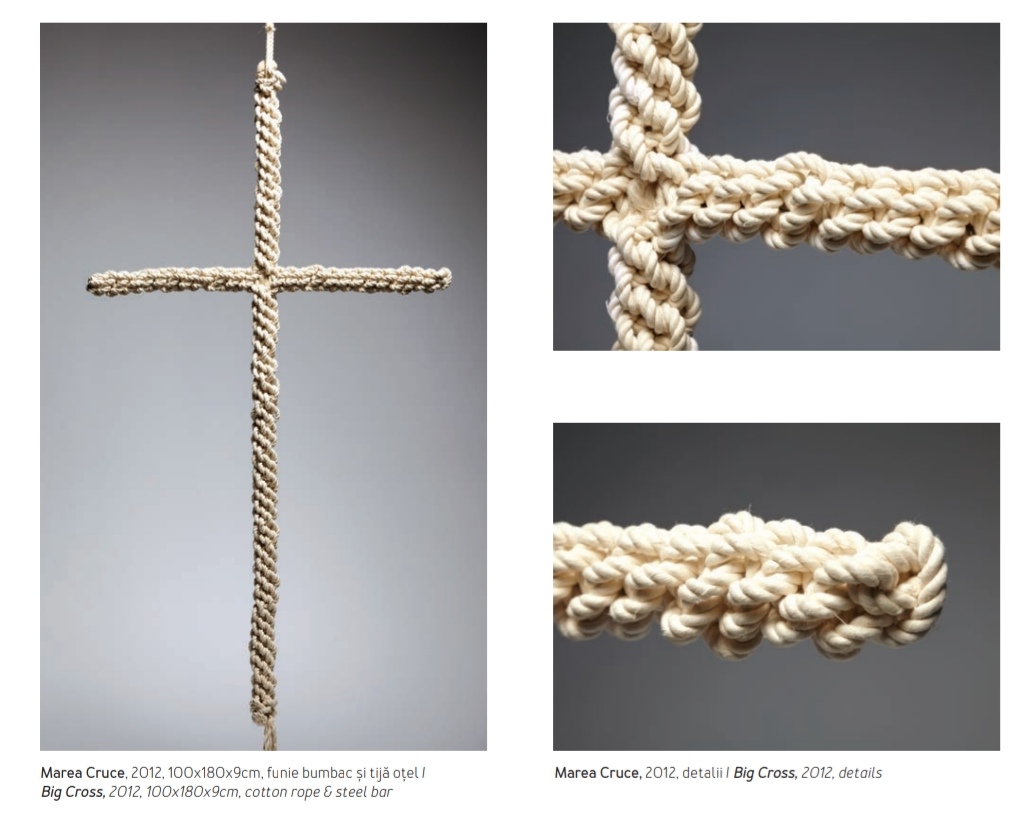

I will exemplify these themes through several works, exhibited in my Bucharest workshop, from Malmaison, which I will describe. In 2011, I recreated the Crown of Thorns of Jesus from thorns painted white in the work Untitled. Even during the creation process, I encountered difficulties because I pinched myself very hard when I wanted to make it. Another Christian symbol is highlighted in the Great Cross work, made in 2012, from four cotton ropes of 20 meters each and a steel rod totalling 180×100 centimetres. The idea started from the multitude of small crosses that taxi drivers hang on the windshields of their cars.

Regarding the family theme, there is a representative work in the workshop entitled Parenthood. The work has three elements in its composition: a bird’s nest found during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic, a chandelier restored by nickel plating with copper and a stuffed pot. The chandelier dates from the turn of the century, 1910-1920, and is perfectly functional today; its brilliance symbolizes the sumptuous place where it could have been placed. However, I attached the nest and the open-beaked owl on one of its arms. The bird was defending its nest, expressing (through the unheard cry) the desperation of abandonment. Here, we can see the antithesis between preciousness/ beauty/ elegance and civilization/ wildness. Even if the environment in which the chandelier is placed might have luxurious or rococo touches, a hawk will only make its nest in a deserted place.

Another theme was presented in the last exhibition – A Whole Day Together – at the Anca Poterașu Gallery. Several paintings featured abandoned swings and playgrounds or very shiny slides that appeared and disappeared in post-apocalyptic nature.

R.E.P.: Do you consider that through the themes addressed, your (ephemeral) objects freeze a certain essential sequence of your life in time?

Z.B.: Themes such as ephemerality, perpetuity, and cyclicity simultaneously were a source of debate for me. I have several paintings depicting the seasons, their passage and return, as I really like the idea of passage. Many times, I ask myself, “What remains?”, “Who are we?”, “What purpose do we have?” are questions that remain unanswered, but I have translated them into the work on the wall, which depicts a sky starry: Eon, 2015 (oil on canvas).

Zoltán Béla, Eon, 2015, oil on canvas, 70x155cm. Image credit: New Folder.

From a relic to an object of contemporary art.

Interview conducted by Raluca-Elena Popa (Scenographer and PhD student in Visual Arts)

Photo credit portrait Zoltán Béla.